Not Just for Triads: Hong Kong’s Unique Style of Tattoos

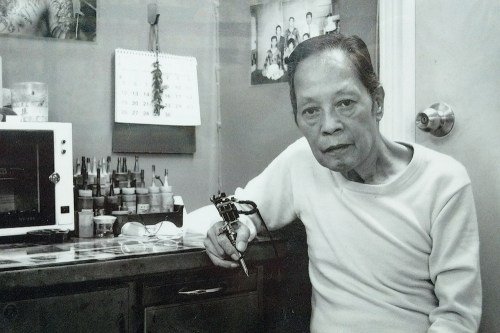

Neon bleeds into shifting drizzle on Portland Street as we enter a discreet doorway. A tattooed arm coaxes a key into the lock, then swings open a windowed door to reveal walls swirling with dragons and stalked by jungle cats amongst unfurling calyces of peonies and roses. Concupiscent nymphs repose amidst Oriental clouds. Daggers draw blood that spills like water over the lip of a cup. This tattoo flash represents a lifetime of work by renowned tattooist Jimmy Ho, who has been putting ink to skin since 1958.

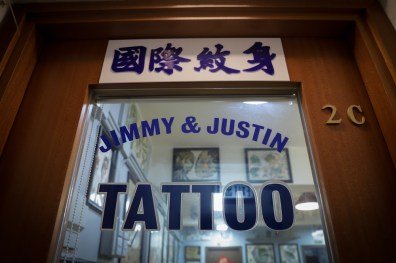

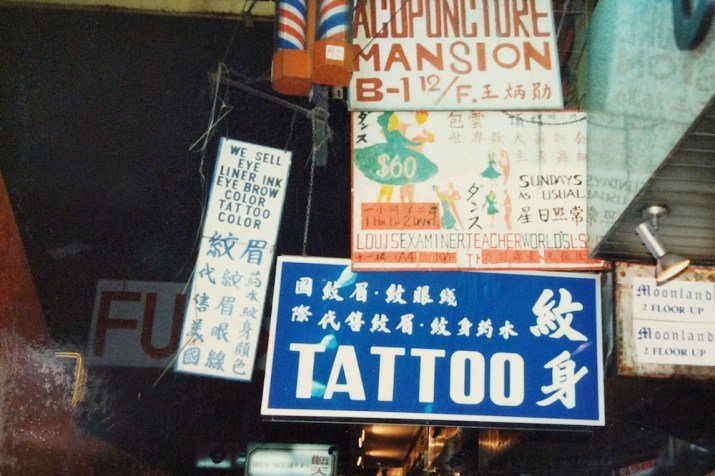

The shop is called Jimmy & Justin Tattoo, and we are welcomed in by Ho’s protege, Justin Ng, who has run the business since Ho retired last year. He draws a cheek-hollowing hit from his cigarette and settles onto a stool, preparing to relate the unlikely tale of an art that was once relegated to the fringes of Hong Kong – but which now colours mainstream society in a way that nobody could have imagined decades ago.

Jimmy Ho’s father was named James, and he was a Shanghainese marine engineer in the merchant navy. Voyaging across the Indian Ocean in 1940, the senior Ho’s ship was torpedoed by the Japanese navy. Clinging to the wreckage, the seaman was rescued by an American warship and brought to Calcutta. There he made a discovery which would leave an indelible mark on Hong Kong. “He saw people doing hand poke tattoos,” explains Ng. “He came back and made a tattoo machine with bike chains and other parts.” He had already collected many designs.

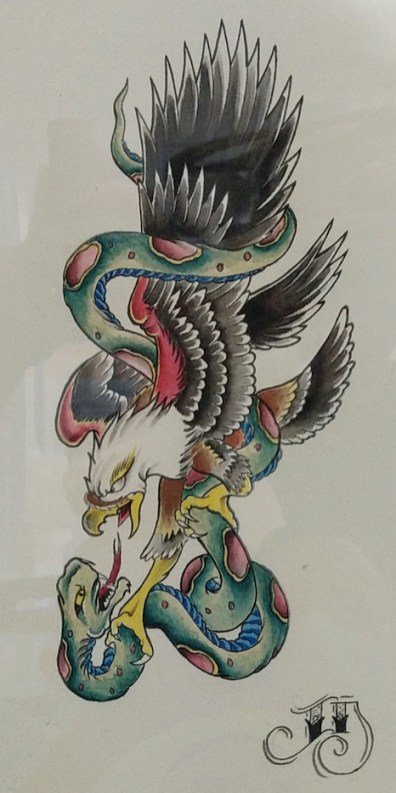

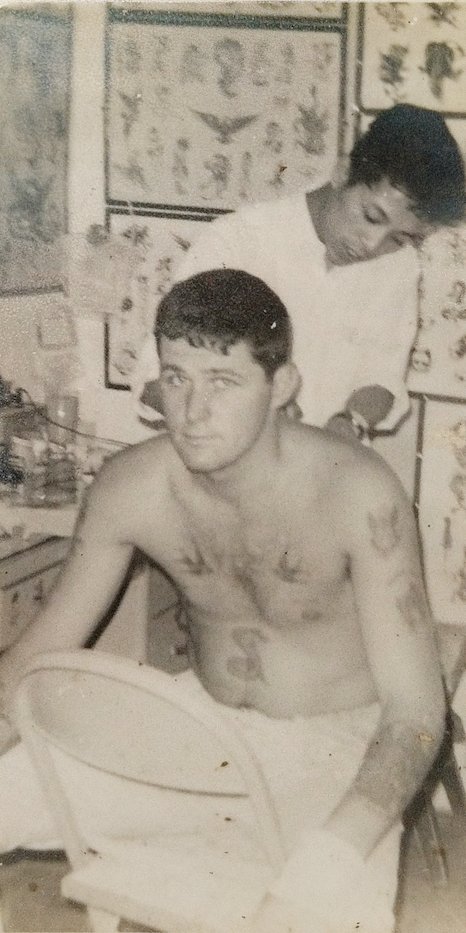

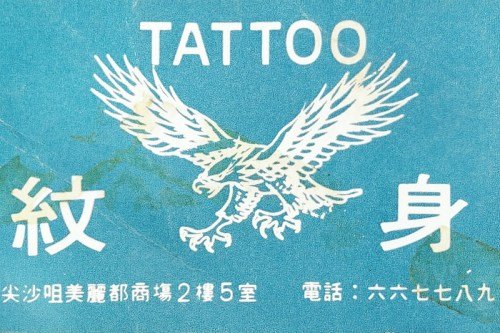

As you might expect for a mariner, Ho had been exposed to archetypal sailor’s tattoos, which collectively fall into the American Traditional genre of tattooing. Hearts, flags, daggers, eagles and baroque nudes rendered with thick outlines and vibrant colours – these are some quintessential examples of the style, which Ho adopted when he opened Rose Tattoo Studio in 1946, shortly after fleeing civil strife in Shanghai, where he had been running another tattoo parlour since the end of the war. Based in Tsim Sha Tsui’s Rose Hotel, the shop flourished, serving American sailors and servicemen looking for souvenirs as they passed through during the Korean and Vietnam wars.

For these men, the point of acquiring ink was to show off where they had been, the same way travellers might plaster their suitcase with stickers. They were obliged by Hong Kong tattooists who adapted the American style by introducing imagery such as dragons, koi and tigers, bringing with them oblique conventions, symbolism and references from Chinese culture.

Ng points to a snarling tiger, its pelt barred with savage geometry the colour of burned wood. “We tattoo tigers going downhill, signifying that they are hunting,” he says. “A tiger going uphill is returning to his lair, defeated. It means you’ve sau1 pei4 (收皮) – failed or given up.”

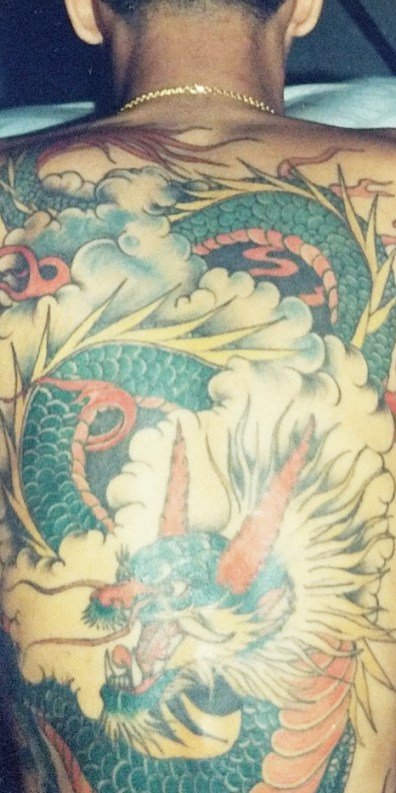

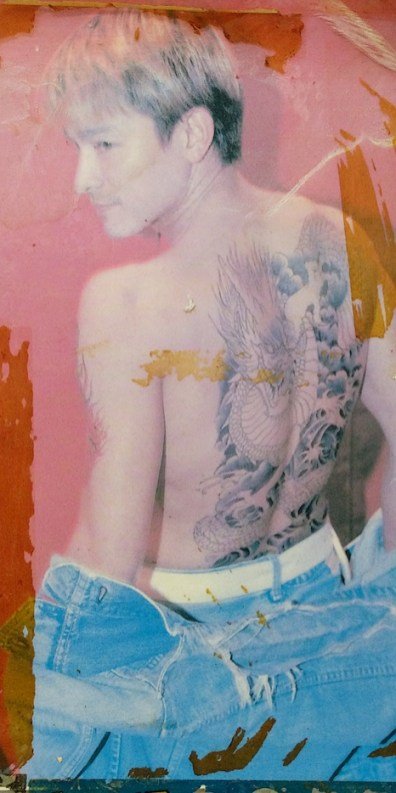

Representing power and luck, dragons are the apex cryptid amongst Hong Kong’s imaginary beings. The taxonomy of Asian dragons is varied; Hong Kong’s species generally have four claws and short mouths, says Ng, while Japanese dragons have three claws and long muzzles. Since imperial times, claws have denoted rank and tattooing a five clawed dragon is considered gauche. “Only an emperor’s dragon should have five claws,” says Ng. “It’s too much. You can’t just erase a claw on a day when you’re feeling less arrogant.”

Traditions are important – but can be defied. “I’d like to buck convention a bit,” says Ng. “These days I’d do tigers going uphill because the poses are dynamic. Jimmy taught these rules but it’s up to me if I want to follow them. I agree with some old practices.”

One tradition that some practitioners adhere to is the prohibition of tattooing Kwun Yum (gun1 yam1 觀音), Kwan Kung (gwaan1 gung1 關公), Buddha (fat6 佛), and other gods. Many consider them off-limits, especially on someone’s back, for fear of disrespecting the deities by crushing them when they lie down.

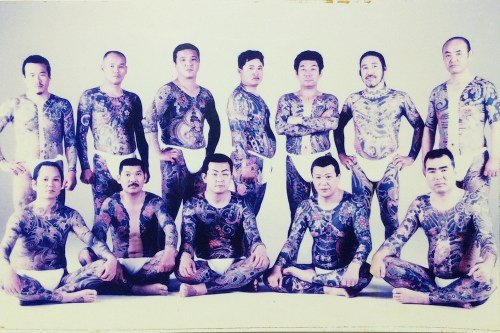

Hong Kong tattoos are often compared to the Japanese Traditional genre, which is characterised by unified pieces covering the body with imagery influenced by woodblock prints. This has had an influence on Hong Kong tattoos, as artists like Jimmy Ho and Pinky Yun blended Japanese and American techniques. “[The tattoos] started out simple and American but Jimmy incorporated the Japanese aesthetic and his own flair,” says Ng.

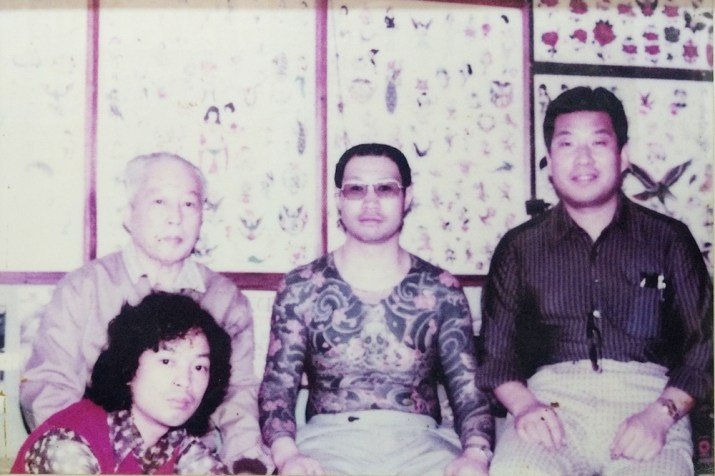

Hong Kong’s relatively young tattooing tradition mines distinctive Chinese mythology and history, with stories like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey to the West being popular subject matter. “American roots, Japanese influence, Chinese subject matter. Yeah, that’s it,” says Jon, also known as Jonny D, who studied under Jimmy Ho and is now the proprietor of the Dragons Lair Tattoo in Central. Jon cites Japanese tattooist Horiyoshi III as another influence. “In the 90s Horiyoshi came to Jimmy’s shop quite a few times, and Jimmy went over to Japan as well,” he says. It is clear that the two artists had mutual respect but the extent to which they may have influenced one another is unclear. “You can see how Jimmy has brought some Japanese elements into his work but he’d do it in his own style.”

The visual splendour of homegrown arts, architecture, folk tradition and ceramics also inspire Hong Kong’s tattooists. The sumptuous curves of a porcelain vase and the sensuous line of a temple’s roof echo human contours. “You know when you go to a temple and you see all the dragons going round the building and pillars – those designs just seem to be made for tattooing,” says Jon.

Despite local tattooists’ enthusiasm for Hong Kong culture, the admiration is not always mutual. The art form has historically been associated with aggressively tattooed gangsters, which has given tattoos both a mystique and a menacing aura. “For sure, I’ve tattooed triads – I tattoo everyone,” says Ng. “Nowadays triads tend not to get inked and if they do, it’s in the mainland where it’s cheaper.”

Each triad clan has distinctive designs but Ng declines to go into detail describing only the most classic. “Most common is to have a dragon on the arm, its head beginning at the heart and going over a shoulder, usually stopping after the bicep so that it peeks out from under a t-shirt. That or a huge dragon on the back or a pair of eagles on the chest. They like dragons best because they signal power and status – only a daai6 lou2 (大佬, “boss”) can get inked. Rank and file members (maa5 zai2 馬仔) aren’t allowed tattoos!”

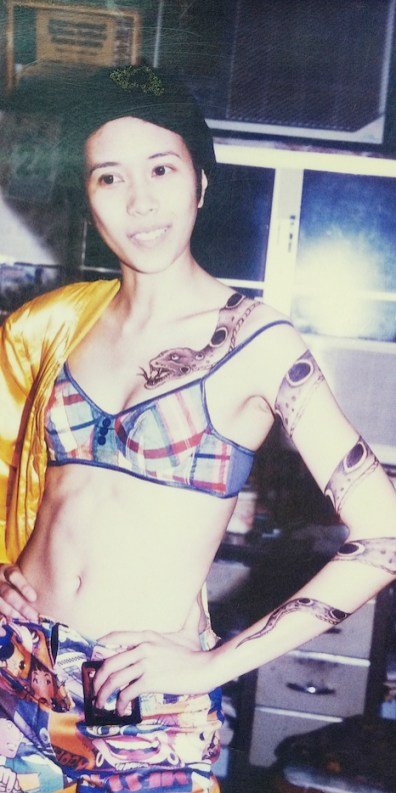

Ng illustrates what he means with a photo of megastar Andy Lau, who is gamely mugging for the camera while showing off a heavily daubed body – ephemeral art painted by Jimmy Ho for a movie. A neighbouring photograph shows Simon Yam with a ferocious tiger and dragon squaring off on his chest, while another features Karen Mok, with a bored snake meticulously rendered across her lithe frame.

Despite their reputation, most people who have these kinds of tattoos are ordinary men and women. They are often seen on the sweat slicked torsos of truck drivers and construction workers. “They’re completely black. Just outlines. No shading,” says Ng. “The first tattoos like that weren’t a deliberate stylistic choice, they were simply unfinished.” This was because the client either ran out of money or couldn’t be bothered to attend follow-up sessions. “They think, ‘You can see it’s a dragon – good enough,’” he says.

With criminal associations waning, and minds opening, Hong Kong tattoos are becoming a distinct genre and growing in popularity. Here and there a quiet office lady fancies a serpent round her arm. They have had some remarkable artists to choose from. High demand for James Ho’s work at Rose Tattoo meant he needed a steady stream of apprentices. Notable alumni include Pinky Yun, Lai Shue-keung (also known as Swallow) and Benny Tsoi.

Yun was the first apprentice. Ho found him working as a shoe shiner, and he noticed that Yun was drawing on walls in between customers. He was impressed by his skill. Eventually, Yun opened Ricky and Pinky Tattoo, a Wan Chai landmark known for its prominent sign and photos of elaborately ornamented biceps, pectorals and pudenda calling out to the boozy masses on Lockhart Road. His partner was Ricky Lo, an apprentice who later took over the shop when Yun immigrated to the United States.

Apprenticing in Hong Kong requires years of unpaid drudgery. Because Rose Studio was such a success, Jimmy Ho’s stepmother didn’t want him to follow in his father’s footsteps – because she wanted her own children to become James Ho’s apprentices. But Jimmy Ho insisted. “Jimmy was only 10 or 12, always learning in secret,” says Ng. When he was caught by his stepmother, she beat him with a shoe and made him clean the floor. Ho slept in the shop and clandestinely tattooed clients who showed up after hours. In the morning, Ho presented the night’s earnings to his father. “You’ve got balls,” James Ho conceded. At the age of 14, with a gift of two tattoo guns from his father and a loan from the family’s housemaid, Jimmy Ho opened his own tattoo shop on Ashley Road. The teenage master outlined tattoos while apprentices coloured and shaded. “Customers would sit there drinking beer and they’d work in a production line,” says Ng.

Not much had changed by the time Ng became Ho’s apprentice. “He’s extremely strict,” he says. “When scolding you he would really yell. Jon reports much the same, laughing at the memory. “There were times when I’d spent all day on something and he’d say, ‘No! That’s wrong! This looks stupid!’” he says.

Apprentices slavishly reproduced their master’s designs. “You start off with simple stuff like roses or old school sailor tattoos,” says Jon. “It gets imprinted in your muscle memory. I also do Chinese painting and it’s very similar.”

Beyond light instruction and occasional upbraidings, the master said no more than “good morning” and “bye-bye” to Ng for years. “He only deigned to speak to me after I started tattooing customers,” he says. In this way, Ho weeded out acolytes who lacked skill and tenacity. Ho’s respect might be gained if a disciple lasted for two to three years, then they would progress to ink and a small bamboo brush, which trains the hand to be light and steady. Practising on pigskin from the wet market, apprentices would become accustomed to the pressure of a needle on flesh. “It was two years before he let us loose on people,” laughs Jon. “Someone coming in for a little tribal thing. He’d outline it and say, ‘Fill that in.’ Something you couldn’t mess up.” By the end of their training, tattooists dispense with templates in favour of ballpoint pens and wield their tattoo guns freehand.

The bold, detailed artwork of Hong Kong tattoos speaks to their roots in the liminal spaces between cultures and conflicts. “I’ve seen many different trends come and go like that,” says Jon, punctuating the point with a snap of his fingers. “People are getting [those] covered up now, but the Asian style is timeless.”

“I hope more people will come to appreciate the style and won’t think of these tattoos as gangster totems – just that they are beautiful,” says Ng. In a landscape of competing fads, ill-advised watercolour and tribal tattoos prove more permanent than their appeal, but Hong Kong tattoos remain. The burning vehemence of a dragon’s eyes is irresistible. Now breaking free from criminal associations, Hong Kong’s tattoo artists have most definitely left their lairs – and they are on the hunt for fresh skin.