Young Bruce Lee, Part II: The Man Before the Legend

Bruce Lee was born on November 27, 1940, and in honour of what would be his 80th birthday, Billy Potts spoke with many of the friends and associates who knew him as a young man during his years in Seattle. This is the second part of his story; read the first part here.

Firecracker smoke climbed the cool evening air as Lilly Woo left the stage. Poised before his Chinatown Night audience, Bruce Lee was dwarfed by three men: Taky Kimura, Jesse Glover and Skip Ellsworth – his students. Dressed in a black kung fu uniform, the diminutive Lee turned within himself, gathering intensity like a rolling storm until he exploded into a blur of motion. Moving into a Praying Mantis form, Lee’s fists made the air pop as he punched vacuums into the atmosphere, stopping millimetres from impact.

Six months earlier, the fists had not stopped when Lee reluctantly acceded to a bare knuckle bout in a YMCA handball court with a fellow Edison Technical student – a karateka (karate practitioner) whom Lee had dropped with a final kick to the face, cracking his skull about the eye and down his cheekbone. The challenger hit the floor and lay still for a long time. Lee and his students thought he was dead. Eventually reviving, the karateka asked how long the fight had lasted. Feeling bad, one of Lee’s students told him it had gone for 22 seconds. In truth it had been roughly half that.

That encounter was fresh in Lee’s mind on Chinatown Night, when his friend, Jacquie Kay, informed him that someone had seen his demonstration and was looking for him. Lee was wary. He finally caught sight of the stranger a week later, at the Japanese community’s Bon Odori block party. The man was fair haired and broad shouldered. Built like a boxer. Approaching from behind, Lee tapped him on the shoulder. “I heard you were looking for me,” he said. Lee was ready to parry or strike, but he assumed a relaxed stance when the towering figure turned around and awkwardly offered his hand.

The stranger was Doug Palmer, then 16 years old. His memory of the encounter is still fresh. “There’s this Chinese guy with hooded eyes looking at me [and] it clicked that this was Bruce,” he says. Palmer had never heard of kung fu until the exhibition. Blown away by what he had seen, he asked Lee if he would teach him. “Come to our next practice and check it out,” Lee replied. “If you’re still interested, we’ll see.”

Learning from Bruce Lee

13-year-old Roger Kay climbed into his father’s car and they lit out for Seattle’s eastern border as they did once or twice weekly. Bundled in with them was Doug Palmer. Travelling down a dirt road, the party arrived at a remote log cabin with a scrubby yard more dirt than grass. There, Lee’s motley assortment of acolytes practised Wing Chun at full speed and strength – but with pulled punches. Palmer and Kay were the youngest students in the class, although Lee wasn’t much older than them; the rest of the students were several years his senior. They called him sifu—master—nonetheless.

Each lesson concluded with meditation. Far from the disapproving eyes of Chinatown’s old guard, Lee nurtured his eclectic crew and his following swelled as he recruited with demonstrations. At one such demonstration, Sue Ann Kay—Jacquie and Roger’s sister and Lee’s first female student—hurled him over her shoulder. He got up and addressed his audience. “Even a girl can do this!” he exclaimed, gesticulating at the petite Kay.

These kinds of theatrics were typical for Lee, who had been developing his acting chops since taking his first steps towards teaching with a rudimentary judo class for the children at Ruby Chow’s. “Everybody got promoted except me,” remembers Wendee Wong who was 10 when she attended that Sunday morning class with her brother, Don, and their cousin, Trisha Mar. Lee knelt down next to the crestfallen little girl and encouraged her to show him her judo skills. “He flew over my shoulder and I thought ‘Wow!’ But I knew he did it on purpose. I didn’t get a different coloured belt but I sure felt good that day.”

Lee’s teaching progressed and he opened a kwoon (gun2 館), a martial arts studio, in Chinatown at 420½ 8th Avenue South. In this dirt floored basement, cameras and kung fu formed an easy partnership as they would for the rest of Lee’s life. In one Polaroid snapped by Lee, Doug Palmer strikes with his right fist as Kay, blurred in mid kick, parries the blow. Dotted arrows travel across the image, telegraphing the sifu’s instructions to block a little higher and to deliver a brisk foot to the groin. “He was always doing that on the photographs,” says Kay.

Love and philosophy

Along with the physical component, Lee had been espousing philosophy in his kung fu classes for years. “The part that I feel is really important in my life was his introduction to Chinese philosophy,” says Sue Ann Kay. Lee’s lectures were wide ranging in content, going from the concept of yin and yang and aspects of the Dao De Jing to acupuncture and even how to use an abacus. He managed to tie all of this back into kung fu. “His demonstrations were just so artistic and beautiful,” Kay remembers wistfully.

Philosophy would come to change Lee’s life in a way that he wouldn’t have imagined. Invited to Kay’s high school to deliver a lecture and demonstration, he was spotted by a cheerleader, Linda Emery. Many years later, contributing to a memoir of her classmate, Jimi Hendrix, she would write: “I first saw my husband-to-be, Bruce Lee, in the hallway of Garfield.” Living just a block away from the Kays, she asked her friend, Sue Ann, who the enigmatic stranger in the hallway had been. “I said he was my gung fu teacher,” Kay recalls. “So I invited her and she came one morning.”

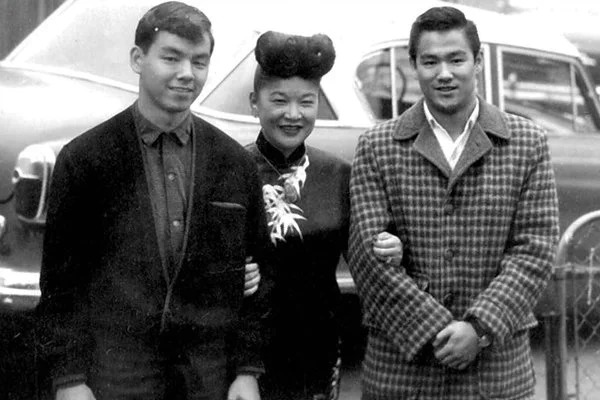

Sue Ann Kay, Bruce Lee and his first assistant instructor Taky Kimura, pose for the camera – courtesy of Sue Ann Kay

An intellectual awakening

Whilst Lee established himself as a teacher, he was still growing into the influential man he would become. In the spring of 1961, he was admitted to the University of Washington’s drama programme, and his academic interest would soon extend beyond theatre to philosophy, psychology and other subjects.

“Of course he made a big splash at the university,” says Lilly Woo, who was attending at the same time. Sue Ann Kay and Emery had also been admitted to the university by this time; they and the rest of Lee’s gang sat at their customary table in the Husky Union Building, known by students as the HUB. A crowd often gathered around Lee. He relished making a show of arm wrestling football players. “He loved to show off,” laughs Woo. “Bruce was only five foot eight but of course he would beat them, these big guys.” Not content to confine competition to roughhousing, Lee, Kay, Emery and the football players also played bridge.

“This was the circle of titans going at each other,” recalls Jacquie Kay. Lee had opted for several of the same courses as Jacquie and saw her almost daily. “There’s a story that those were hard years for him at the university in terms of being a student,” she says, but that wasn’t what she observed. Cutting about the cherry blossomed campus in Wayfarer sunglasses and a varsity jacket, Lee embraced life and community at “U Dub,” as the university is affectionately known. He flourished by flowing around obstacles. “The bamboo or willow survives by bending with the wind,” he would have said at the time, still ironing out his talent for delivering quotable maxims.

Kay and Lee shared Chinese language and philosophy classes. “Our term paper was on ‘Our View of Chinese Philosophy,’” she says. “I really went deep into the philosophy with my heart.” By contrast, she recalls, Lee’s paper was “verbatim” Alan Watts, the British counterculture philosopher who had popularized Eastern philosophy for Western audiences with his pithy writings. While Kay got a B, Lee scored an A+. Incensed, she railed at Bruce, who smiled and said, “You should have done something simple.” With hindsight, Kay says “Bruce understood how he could get his message across, and he knew best the kind of language that would work with people.”

Doug Palmer, Bruce Lee and friend in Hong Kong, 1963 – courtesy of Doug Palmer

Return to Hong Kong

By 1963, Doug Palmer was pursuing Chinese Studies at Yale. He returned to Seattle for the Christmas holidays where Lee presented him with an invitation. “He had not been back to Hong Kong since he left in ‘59 and he invited me to go with him,” he says. Palmer accepted enthusiastically and found himself, the following summer, in the Lee family’s Jordan apartment.

“It was hot as hell. And humid as hell. And there was a drought,” says Palmer. Every receptacle and bathtub in the Lee household was filled with water when it ran once every four days. Nevertheless, Lee and his family showed their friend the town. Palmer was impressed. “It was fantastic. [They] took me up to the Peak, out to Aberdeen, all over the New Territories. We ate, went out for massages, everything you could want to do.” Lee was back in his element, but his family noticed that he’d changed. The hot tempered youth who had left for the States, had returned more restrained, less impetuous.

Returning home one evening, Lee boarded the Star Ferry. As the ferry’s prow split the harbour, he was accosted by two youths. “Bruce, at that time, was very fashion conscious and had suits made,” explains Palmer. “He liked to design the cut of the collar and the lapels. These two guys thought he looked like a fop.” They taunted Lee, but he ignored their baiting and disembarked at Tsim Sha Tsui, passing the Kowloon-Canton Railway station and continuing up a neon-lit Nathan Road. His tormentors followed.

“Where you rushing off to? You gotta get home to mamma?”

Lee ignored them for another few blocks until he didn’t want to take it anymore, so he whirled around and “kicked the guy closest to him in the shin,” says Palmer. The youth crumpled to the pavement and his comrade backed off. Hearing the story later that night, Lee’s cousin Frank chuckled. “If that was four years ago Bruce would have left both of the guys bloody and in a pulp on the sidewalk. He wouldn’t have just kicked one guy quickly and left it at that. I guess he’s grown up a little.”

Bruce Lee’s older brother Peter Lee, Ruby Chow and Bruce Lee in the beginning, 1959 – Bruce Lee Family Archive

Change on the horizon

Back in Seattle, summer ripened into crisp fall, rich with petrichor and cloaked in hues of red and gold against a deliquescent sky. At 1122 Jefferson Street, relations between Ruby Chow and Lee had become strained. “They were both alpha personalities,” explains Doug Palmer. “In her mind, Bruce was a freeloader. A young whippersnapper that didn’t know his place and he thought she was overbearing. He was counting the days when he could move out.”

Lee had had one foot out the door for some time, and had begun construction of a new kwoon in the University District, but work was not complete. With little other choice, he called Doug Palmer’s mother. “I’m moving out, can I come over?” he asked. He stayed with the Palmers for two months until his kwoon was ready.

That November, Lee marked his 23rd birthday in his gleaming new kwoon. The 3,000-square-foot space was a far cry from the basements and yards where he had previously taught. “That was a beautiful facility,” Sue Ann Kay remembers. “He had an apartment in the back of the studio. It was a nice place. I remember saying ‘Wow!’” Clean and modern, Lee offset the minimalist space with carved dragons wrapping sinuously around wooden furniture that he’d had brought over from Hong Kong.

Kay and Emery had enthusiastically arranged a cake with candles, cards and gifts. They sang him ‘Happy Birthday.’ Lee, though surprised and appreciative, seemed uncomfortable. “I don’t know,” says Kay with a shrug. “He wasn’t used to hearing ‘Happy Birthday’ in English and he didn’t really seem to like being the centre of attention that way, or maybe a birthday cake was foreign to him.” Lee cut the tension by putting on a cha-cha record and dancing.

It may have been that the passing of another year brought with it possibilities but also uncertainty. Lee’s time in Seattle was drawing to a close. “When you drop a pebble into a pool of water, the pebble starts a series of ripples that expand until they encompass the whole pool,” Lee had written to his friend, Pearl Tso, a year earlier. “This is exactly what will happen when I give my ideas a definite plan of action. Right now, I can project my thoughts into the future, I can see ahead of me. I dream (remember that practical dreamers never quit). I may now own nothing but a little place down in a basement, but once my imagination has got up a full head of steam, I can see painted on a canvas of my mind a picture of a fine, big five or six story Gung Fu Institute with branches all over the States. I am not easily discouraged, I readily visualize myself as overcoming obstacles, winning out over setbacks, achieving ‘impossible’ objectives.”

Lee would be gone with the next spring, moving south to Oakland and leaving familiarity to realise his vision.

Reunions and goodbyes

Before leaving, Lee made a final visit to Ruby Chow’s to say goodbye. “It was a Saturday just before I came to work,” recalls Trisha Mar. “Cheryl got several pictures [with him]. She was bragging that she had her picture taken with Bruce and I said ‘Oh, why didn’t you guys wait for me?’ I never got to say goodbye or [say] ‘See you again.’ I never saw him again.” She sighs.

Cheryl, Ruby Chow’s only daughter, was athletic and artistic, and Lee had had a special affinity for her. Cheryl had loved to dance and play practical jokes with Lee. Many years later, she would again be one of the last of the Seattle contingent to see him. That final encounter happened nearly a decade after Lee left Seattle. In 1972, Seattle’s Chinese Community Girls Drill Team was in Taiwan to march at Chiang Kai-shek’s fifth inauguration as president. Cheryl Chow and her cousin, Wendee Wong, were amongst them.

“Seven of us wanted to go to Hong Kong. It’s only an hour away [by plane],” recalls Wong. Exploring Kowloon, the girls suddenly heard a familiar voice calling: “Cheryl!” Spinning around they saw their old friend: Bruce Lee. Dressed in a singlet and aviators, he looked every inch the movie star he had become. The friends embraced, improbably bridging the ocean of time and space that had come between them.

In the intervening seven years, Lee had realised his ambition of opening a school and created the hybrid martial art, Jeet Kune Do. He had forged a career as a filmmaker. With three films complete, he was on the cusp of international success with Enter the Dragon, which would be released the following year. He was working on what he intended to be his magnum opus, Game of Death. He had married Linda Emery and the two had started a family. He was now a father of two.

“They hadn’t seen each other for a while. Someone took a picture of them and those two were in the Hong Kong newspapers the next day,” says Wong with a smile. “We went to eat and he got to chit chat with her for a little bit.”

The following year, Lee died from an allergic reaction to a painkiller. He was 32 years old.

After his departure from Seattle, the people who had grown up with Lee moved on, building their own lives and families. Occasionally they had heard about their old friend and his triumphs. They cheered him on, thinking back on the time they had shared, but none got to say goodbye. Contemplating what each would say to Bruce if they could speak to him once more, video calls with these old friends and acquaintances fall momentarily silent.

“Bruce! I’d like to redeem myself. I think I could flip you over my shoulder again!” laughs Wendee Wong.

“How about a race?” smiles Greg Luke.

“I would share with him what I’ve shared with you. The influence that he’s had on my life,” says Sue Ann Kay.

“It’s amazing what he’s done for Chinese people,” offers Brien Chow, while Betty Lau chips in that “Bruce really improved the situation for young Asian Americans.” On what he has done, they both agree. “He’s given them a lot of pride,” they say, almost in unison.

Vi Mar’s message is simple: “Bruce, your Auntie Vi is proud of you.”

The conversations end with thoughts of the hero from the old neighbourhood. The young man from Hong Kong, despite all his speed, caught in memory, surrounded by friends. Not an icon or a movie star. Just Bruce. He regales them with a joke, a playful sideways glance and a smile with its warmth and mischief that could never be fully captured on celluloid, at least not to those who knew and cared for him.

Bruce Lee at Lake Washington, photograph gifted to Sue Ann Kay by Lee – courtesy of Sue Ann Kay